|

Curly Bear Wagner

speaks about the

Canadian fur trade.

|

|

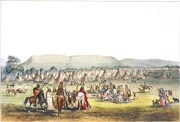

In October 1754 hundreds of Kainah, or Blood, people camped on

the Saskatchewan River, watched Anthony Henday and his Cree guides

enter their camp and walk through the esplanade created by 200

tipis, pitched in two long parallel rows.

|

Piegan camp, ca. 1900.

|

Edward Curtis image

Courtesy of Northwestern University Library.

|

Their horses, tethered to the lodges, would have whinnied as these

strangers walked among them. From the great lodge at the end of the

street, the chief and 20 elders waited for their visitors.

Inside the lodge the strangers were seated next to the chief. The pipe was passed

around in silence, then willow baskets full of boiled buffalo tongue were shared.

After these gracious formalities were completed, Henday told the men of his purpose

and invited the chief to send young men to Hudson's Bay to exchange their furs

for rifles, tobacco, blankets, ammunition, colored cloth, and beads.

The chief waited politely for the interpreter to complete his signing

of the message, then told the visitor how the Blackfeet were horsemen,

not accustomed to canoes; they ate meat, not fish; and they had heard

about Indians who starved while making their way to the trading posts.

These were serious problems, and besides, they had no need for the

goods Henday described. The buffalo provided all they could ever

want, and their bows and arrows were all they required to obtain

their prey.

"The inhabitants of the Plains are so advantageously situated

that they could live very happily independent of our assistance. They

are surrounded with innumerable herds of various kinds of animals, whose

flesh affords them excellent nourishment and whose skins defend them from

the inclemency of the weather, and they have invented so many means for

the destruction of animals that they stand in no need of ammunition to

provide a sufficiency for their purposes. It is then our luxuries that

attract them to the fort and make us so necessary to their happiness" (McGillivray:

1929).

[Duncan McGillivray, clerk for the North West Company, 1794.]

"The Herd," 1860—Martin S. Garretson.

Image courtesy of National

Museum of Wildlife Art.

The Blackfeet, in general, were not beaver trappers

with the exception of the westernmost bands of Piegan. The others

trapped kit foxes and wolves for furs. They were not interested in

completely changing their way of life to enter the trade as offered

by the Europeans.

Gray wolf

Image courtesy of Montana Department

of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks.

Accounts by whites in Blackfeet territory during the 18th century

paint a picture of friendly relationships. The traders who wintered

with various groups of Blackfeet were treated well, and commerce

was brisk. In 1805 the North West Company reported a typical acquisition

of 77,500 beaver, 51,250 muskrat, and 40,400 martin skins in addition

to 1,135 buffalo robes. Similar numbers were reported by the Hudson's

Bay Company. The Blackfeet participated by providing the bison robes

as well as horses for their transport. This business kept them focused

on controlling the buffalo plains and on stealing horses.

However, for a number of reasons, life couldn't continue this way

very long. The year that Lewis and Clark traveled up the Missouri,

the prolific trader David Thompson attempted to cross the Canadian

Rockies to explore the Columbia headwaters, but he was stopped by

the Piegans. As beaver were becoming scarce along the rivers of Hudson's

Bay, traders were sent into new areas, and Cree, Sioux, and Crow

were being pushed further westward into Blackfeet country, creating

new tension and conflict. Four years earlier, in 1801, "the Sakatow

man, the principal chief of the Piegans," complained to Thompson

about arming the Kootenays, whom the chief feared would arm the "Flat

Heads," and all this would cause harm to the Piegans. Any attempt

to establish trade relations with the Kutenai was seen as a direct

conflict with the Piegans.

It was this tense world that Lewis and Clark passed through in 1805. |