|

| |

Piegan horses and travois, 1900.

Image courtesy of Glenbow

Archives NA-1700-142. |

| |

|

| |

Arrowleaf balsamroot

K. Lugthart photo |

| |

© Lynn Kitagawa

used with permission |

| |

Pasque flower

K. Lugthart photo |

| |

Blooming prickly pear.

Image

courtesy of K. Furrow. |

| |

© Lynn Kitagawa

used with permission |

| |

Rosehip

K. Lugthart photo

|

|

|

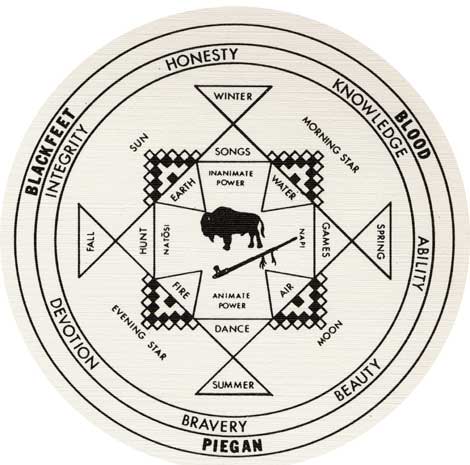

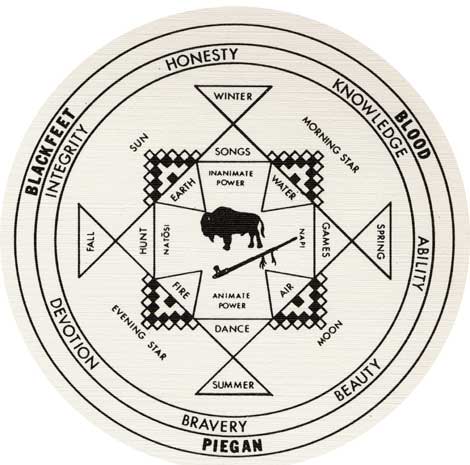

Great Falls > Culture > Camp Life & Seasonal Round

©Jackie Parsons- used with permission

Don Parsons- artist

The yearly cycle of the Blackfeet is divided into four seasons. In

the days when buffalo still roamed the land, patterns of movement reflected

the location of important foods. The buffalo was most important, but

particular camp locations were selected with other resources in mind

as well. To an observer, the changes in camp locations through the

year may appear random, but they were far from that. Each location

was known for the resources it held, whether they were plant, animal,

or mineral, and year after year, the people returned to these locations.

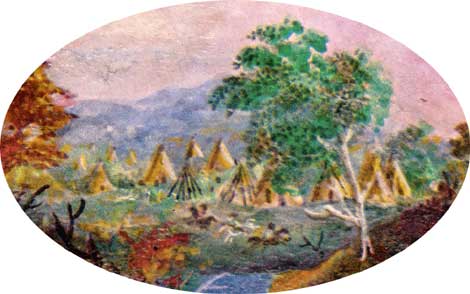

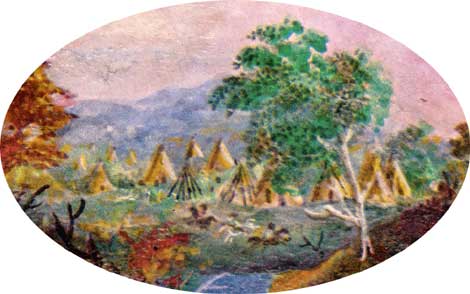

Piegan encampment (Point, 1846)

used with permission from Loyola Press

The work of moving

camp was the responsibility of the women. When the head

chief decided to move camp, that evening the camp-crier would announce

that in the morning everyone should be all ready to leave. The

women were up at dawn preparing the family breakfast, finishing

packing, and tying the family belongings to the horse travois.

| Women would take down their hundred pound buffalo skin lodges

and tie them between the horse's horned saddle. Two horses were

needed to pack the nineteen lodge poles. Women packed saddle bags

filled with dried meat and berries, tallow, and tobacco, and they

packed bedding, tools, utensils, and ceremonial objects to be carried

on the travois. Babies rode on their mother's back while

the toddlers rode upon the travois. Older boys took care of the

loose horses. |

"The horse that carries the calumet on the march

is exempt from all other use and she who leads him is the most

honored woman of the tribe" (Point, 1846). -used

with permission from Loyola Press

|

The day's long journey would end with enough sunlight

so the women could unpack, erect lodges, cook supper, and then prepare

for the next day. Children helped gather wood and bring water. When

wood was low, women used dried buffalo chips and dried grass for fire

(Summarized from Ewers 1958:92-93).

|

| |

| Spring |

| |

Goldeyes

K. Furrow photo |

When spring comes, life awakens and the beauty of green

life can be seen again. Spring arrives just after the moon "when

the ice breaks up" (in April), during the moon "when the geese

come" or "when the leaves are budding" (in May) and after the

first thunder is heard. This marks the end of the storytelling

season.

|

In buffalo days, when the buffalo plant was in flower and the buffalo calves

were yellow, it was time to leave the long camps of winter. Before they

left camp, just after the snow disappeared, the ground of the tobacco garden

was prepared for planting. The seeds would grow while they were off hunting

the buffalo. Some of the important men who were responsible for the well-being

of the tobacco, would return to the garden to tend the plants several times

during the growing season. At the right time, everyone would gather near

the garden for harvesting the tobacco in a ceremonial manner.

Extended family groups would split apart to follow the

buffalo and other game out onto the grassy plains, always choosing

campsites near potable water and firewood. Everyone anticipated

the great variety of fresh foods of spring after eating dried meat

and berries most of the long winter. Great spring feasts included

eggs of ducks and other water-fowl, "pomme blanche," wild

turnip, and roasted camas bulbs.

|

Duck nest

Duck nest

N. Dakota Game & Fish |

|

| |

| Summer |

| |

Wild sunflowers

Wild sunflowers

S. Thompson photo |

The buffalo migrated to the open grassy plains in the

early summer, the time known to the Blackfeet as the "moon of

flowers."

The people followed the buffalo to the Cypress

Hills or other hunting grounds in the eastern region of their homeland

where they would stay only as long as the buffalo. The summer

hunts

provided the ceremonial buffalo-bull tongues needed for the Medicine

Lodge, or Sun Dance Ceremony, during the moon when "serviceberries

were ripe".

|

After the Sun Dance, the chief would tell his people it was time to move

to "Many-berries" or other places rich in fruit. The women would gather

sarvis berries every other year, when there was a crop. They collected

branches, which they beat over a buffalo robe. The berries were dried and

stored for future use. Goose berries and red willow berries were also collected

in late summer. The people would move from place to place either because

it was a good location for picking berries or a good place to hunt bulls. |

| |

| Fall |

| |

|

Buffalo berry

|

Dave Ode photo

|

|

At the time when "leaves are yellow and the time of first

frost" the chief would announce that it was time to move to where

the choke-cherries were ripe. The women would pick the fruit,

then

pound it with a stone maul, pits and all, and then dry it. This

was usually mixed into soup or with pemmican. Bull berries, a

favorite

fruit, were ripe at the same time.

|

"For the superior hunter, the best weapon was

the rifle" (Point, 1846).

used with permission from Loyola Press

|

About the time "when the geese fly south" was the most

important buffalo

hunt of the year. The fall was also a time to go to the

hills and mountains for lodge poles. While men were busy with their

activities, the women processed meat and berries and made pemmican

for the winter. Robes were also prepared for trade.

|

Once the white traders were established in Blackfeet country, the men hunted

for wolves, badgers, skunks, antelopes, and buffalo at this time of year so

they would have hides and pelts to trade. The trading fort was part of their

seasonal round, and they all looked forward to the goods that would be acquired

through trade. |

| |

| Winter |

| |

Winter camp locations were scouted out in October or

November. The head chief would consider the information from the

scouts, then,

with the advice of the band chiefs, select a location that fit

the needs of the tribe. The ideal locations were in stands of

trees

in protected valleys, where people were sheltered from the snow

and cold winter winds. Camps were arranged along rivers for fresh

water and where firewood could easily be found to keep the lodges

warm. The buffalo wintered in the valley bottoms, along with the

Blackfeet, who gathered in large numbers during this season.

|

Old Cabin on Two Medicine River

Old Cabin on Two Medicine River

S. Thompson photo |

At this season, buffalo were prime and fat. Full tribal participation

was needed to conduct a successful hunt and to acquire the winter supply

of buffalo meat. Hunting continued into the moon "when the buffalo calves

are black" and the heavy snows come (in January). When the fresh food

was consumed, people lived off of the dried meat and berries preserved

during the previous months.

Winter days were long and provided a time for the nomadic buffalo followers

to rest and play and pass on traditional stories. Camps were large and

much socializing occurred. The winter was a time for children up to sixteen

years of age to play and compete against each other in traditional winter

sport games, including coasting, top-spinning, sliding on ice, and other

children's games.

"Favorite pastimes of children playing on ice were sliding

or a game called spinning tops." (Point, 1846) used with permission

from Loyola Press On cold, windy nights the children would sit around the warm tipi lodges

and listen to the elders recount the beautiful myths, legends, and stories

of their tribe. The elders would tell the children about their brave Blackfeet

warriors who had many encounters in war against their enemies. Other stories

of exciting hunting trips would help pass the long winter months.

Elders' stories taught how to look into the future by observing the warnings

of animals, and how to know the different moons by watching the changes

of the seasons and by studying the habits of birds and wild animals, and

to know the signs in the heavens.

The most popular of winter sports was coasting down steep, snow-packed

hills onto the valley bottoms. The sleds that were used for coasting were

made without a single nail or bolt. They were made entirely of parts of

the buffalo carcass. The runners were five to ten buffalo rib bones; the

long, heavy ribs of a buffalo cow, scraped free of meat and gristle. These

ribs were separated from the backbone and breastbone and reassembled in

exactly the same order they had appeared on the buffalo. The ribs were

tied together at each end by a rawhide rope that wound in and around a

cross-piece of split willow. The seat was made of skin from the leg of

the buffalo, stretched hair-side up over the runners and tied to the willow

cross bars at each end. A buffalo tail was sewn or tied to the rear of

the seat for decoration. A rawhide rope was tied to the front to pull the

sled uphill and to guide it sliding downhill (Ewers: 1945).

The people have always understood winter as the time for death, when that

spirit from the north blows onto the Mother Earth its power, the snow.

All of the beauty of the Mother Earth is covered over by the snow white

blanket of the northern spirit. Underneath this blanket all life goes to

sleep as though they were dead (Floyd Rider, 1994). All winter long the

Beaver Bundle holders notched into their calendar sticks the passing of

each day, keeping track of the right time for their spring Beaver ceremonies.

|

| |

Background: Rocky Mountain Front, near Skunk Creek. K.

Lugthart photo

|

|

|

|