|

| |

Changes

to Blackfeet Reservation Through the 19th Century

Click on a date to the right of the map to see the extent of the

Blackfeet Reservation at that time. The reservations, as shown in

1895, are virtually unchanged today. |

| |

Badger

Valley at twilight

Badger

Valley at twilight, Ghost Ridge in the distance.

S. Thompson photo |

| |

| Treaty 7 |

| | |

| |

|

| |

Siksika

camp at Blackfoot Crossing, ca.1900.

The signing of Treaty

7 occurred at "Blackfoot Crossing" on

the Bow River, which is located on the Siksika Reserve east

of Calgary, Alberta.

Image courtesy of Glenbow

Archives.

NA-1094-4

|

| |

Portion

of 1888 Dominion of Canada map, showing the section of the Bow River

with Blackfoot Crossing marked.

Courtesy of the Glenbow Museum Archives.

|

|

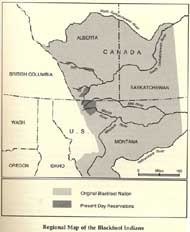

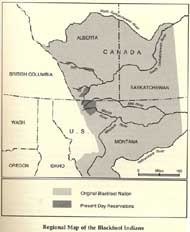

Regional map of

Blackfoot homelands with present day reservations.

(Samek, 1987).

|

|

|

Great Falls > Culture > The Shrinking Reservation

|

Life continued on, much as it always had, for Blackfeet

people for the first years after the Lame Bull Treaty

of 1855. One difference

was the addition of an agent, based at Fort Benton,

who was assigned to distribute annuities promised by

the treaty. The annuities were

not always sent, and after years of trade in buffalo

robes, this mainstay was less predictable. People starved

in 1861, the year

the Mullan Road carried newcomers along the old trail

between Fort Benton and Fort Walla Walla. |

| |

(Raczka: 1979)

(Raczka: 1979)

|

1861 - When they eat dogs.

Again, starvation times. |

|

| |

| Then with the Gold Rush of 1862, the traditional Blackfeet world

began to fall apart. Within a few short years, more than 15,000

miners were working and exploring in and around Blackfeet country.

Some traditional hunting grounds were overrun by miners and diseases,

for which the people had no resistance. Scarlet fever killed more

than 1,000 Blackfeet in 1864. |

| |

| 1865 Treaty |

| |

| In 1865 a small group of tribal leaders agreed to sell their lands

south of the Missouri River to the U.S. government. They sold 2,000

square miles of land for $1 million. The new treaty was never ratified,

but with the assent of the Indians, the Executive

Order of 1873 set apart a reserve for the joint occupancy

of the Gros Ventres, Piegan, Bloods, Blackfeet, and River Crows.

This new Great Northern Reservation, defined by an Act

of Congress in 1874, was in part composed of territory

assigned the Blackfeet by the Treaty of 1855. It did not, however,

comprise all of that territory, for the U.S. government moved the

southern boundary of the reservation 200 miles northward, opening

lands to settlement without any compensation to the tribe. |

| |

| Massacre of the Small Robes, 1870 |

| |

| As pressures grew, so did intertribal conflicts, especially

with the Cree and Assiniboine and with the rapidly growing numbers

of settlers. Some bands tried to avoid trouble, yet the young

men were hard to control during these difficult times. One of

the most peaceful bands was the Small Robes, led by Chief Heavy

Runner. |

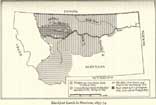

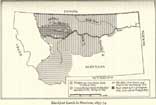

Blackfoot lands in Montana, 1855-74.

Blackfoot lands in Montana, 1855-74.

Ewers, 1958. |

On a cold January morning of 1870, with much suffering

in the lodges because of smallpox,Chief Heavy Runner's

camp was attacked by U.S. troops. A total

of 173 Indians (many of whom were women and children)

were killed in retaliation for the killing of a white

man

by some

young

Piegans.

Some

2,000 Blackfeet died of smallpox

that winter. |

| |

| The Last Buffalo |

| |

The last buffalo hunt took place in 1882, south of the Sweet

Grass Hills. What

Isaac Stevens had predicted–the extinction

of the buffalo–had come true. The Blackfeet became completely

dependent on government annuities for their survival.

Thousands of hungry people moved to the agency on Badger

Creek, yet rations were not available. People starved.

The winter that followed is still known among the people

as "starvation winter." Hundreds of Piegans died. The

ridge behind the agency is still known as "Ghost Ridge"

because so many people were buried there that year.

Since the time of the first treaty, 80 percent of the

Piegans had died, and the buffalo were gone. Life would

never be the same.

"The End", 1913.

Martin S. Garretson.

Courtesy of National Museum

of Wildlife Art.

|

| |

| Act of Congress, 1887 |

| |

| With growing numbers of settlers surrounding the shrinking reservation,

the U.S. government responded to pressure from white ranchers by

negotiating another land treaty with the tribes of the region.

These land

cession hearings were held in the dead of winter, when

many Blackfeet could not attend. A bare majority of Blackfeet leaders

passed an agreement to split the Great Northern Reservation into

three separate agencies and to relinquish all but 45 square miles.

In exchange for $125,000 per year for 10 years, the Blackfeet ceded

17 million acres of their homeland. |

| |

| Act of Congress, 1895 |

| |

One final land cession of the 19th century, the

"ceded

strip," reduced the reservation by another 800,000

acres along the "Backbone of the World." For

the Blackfeet this land was like their church. The mountains

held

gifts from

the Creator, provided for their long-term health and

well-being. Many plants, animals, minerals, and pure

water used in their customary

practices are found there, and the high peaks allow

seekers to reach toward Creator Sun while staying connected

to Mother Earth.

White Calf, the Piegan chief, told the treaty commissioners

how he felt about the loss of these mountain lands and

his other concerns

for his people:

White Calf

White Calf

Image courtesy of Montana Historical Society. |

"Chief Mountain is my head. Now my head is cut

off. The mountains have been my last refuge. We have

been driven here and now we are settled. From Birch

Creek to the boundary is what I now give you. I want

the timber because in the future my children will need

it....The right to hunt...the grazing land...to fish

in the mountains...we will sell you the mountain portion

of our land....We don’t want our Great Father

to ask for anything more. We will have to send you away.

We don’t want our lands allotted....There

are many little children going to school and getting

an education; there is no end to civilizing our children.

They are the ones that will get the benefits from these

lands" (White Calf in U.S. Senate doc. 118: 1896, from

Sept. 1895 proceedings).

|

| The Blackfeet sold this land, now Glacier Park

and part of the Lewis and Clark Forest, for $1.5 million with

the agreement (codified in Article 5) that tribal lands would

not be subjected to allotments. |

Blackfoot Lands in

Montana, 1875-Present.

Ewers, 1958. |

|

| |

| 1912 Allotment of Lands |

| |

"The opening of reservation

lands to settlement was legislated without the

tribe's consent, as per the General Allotment

Act. Each enrolled member of the Blackfeet tribe

was granted an allotment of land within the

reservation. Any lands not accounted for within

this allocation were opened for sale to the

public. A survey of the reservation identified

just over 1.5 million acres, which would be

allocated to some 2,500 Blackfeet, leaving nearly

800,000 acres to be opened for settlement" (Samek:

1987).

Often without Blackfeet participation or agreement, this tribe

lost approximately half its land base, much of it without

compensation.

|

| |

Background: Portion

of 1892 Rand McNally Montana map,

courtesy of Malcolm MacCalman |

|

|

|