|

| |

Narcisse

Blood on story telling

|

| |

| |

| |

Early morning on the Belly River, Alberta.

Early morning on the Belly River, Alberta.

K. Lugthart photo |

| |

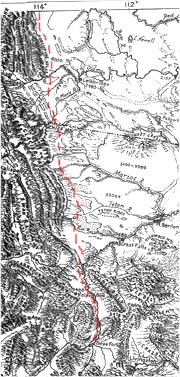

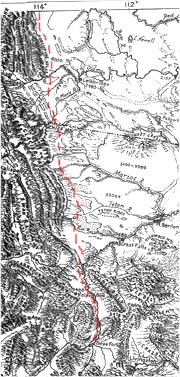

The Old North Trail in Blackfeet country

The Old North Trail in Blackfeet country

Base map adapted from Raisz: 1957 |

| |

Big Spring illustrates the old way of recording Blackfoot

events and history. Glacier National Park, 1913 (Hungry Wolf: 1989).

Image courtesy of Glacier National Park archives.

|

| |

| |

Darrell

Kipp on Piegan history

|

| |

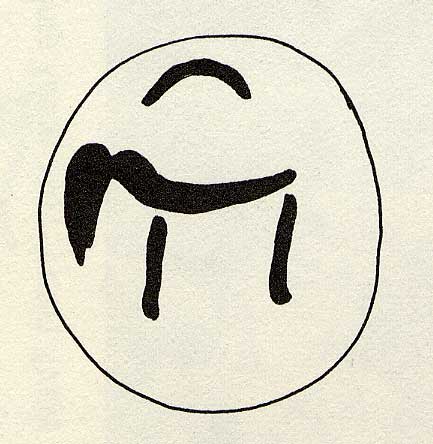

| Sign language for Piegan (Pikuni):

“Piegan (Indian) – Partially close the right hand; i.e.,

keeping backs of fingers form second joints to knuckles about on line

with back of hand, ball of thumb resting on second joint of index; hold

the hand close to lower part of right cheek, back of hand right, edges

pointing upwards; move the hand, mostly by elbow action, in small circle

parallel to cheek" (Clark 1959:302).

|

|

|

Great Falls > Culture > Since Time Immemorial

|

Narcisse Blood,

coordinator of Kainah Studies at Red Crow Community College in Standoff,

Alberta, speaks about "time immemorial" and the way Blackfeet

people understand their history.

|

|

|

| |

| Oral History |

| |

Waterton Lakes, origin of beaver bundle

Waterton Lakes, origin of beaver bundle

K. Lugthart photo Oral traditions include history, stories, and mythology, and

each is different.

History is important to all peoples, and particular methods

are developed by all oral cultures to engage the collective

memory. Oral history is often told in a ceremonial way, with

the history of the people being related through songs, told

in a particular sequence, reflecting their historical relationships.

The words of songs remain the same, even over centuries of

change. By encoding history in songs, the Nitsitapi (Blackfeet)

remember their history from generation to generation.

Stories are always tied to particular people, animals, events,

and places. When Nitsitapi pass a particular place,

they might be reminded of stories of their family and tribe,

of battles with enemies, or of any unusual event that stands

out. These stories are about events that actually happened,

but they are embellished and altered a little with each telling.

In this way, they are different from ceremonial stories of

history.

Myths are another expression of a culture's stories. Although

myths are by definition fiction, they generally hold some

core of fact important to the people. Myths help to convey

the essence of a people, if not the factual history.

Percy Bullchild, a Piegan, explains the importance of oral

history among Blackfeet people:

"We Indians do not have written history like our white friends.

Ours is handed down from generation to generation orally. In this way

we have preserved our Indian history and our legends of the beginning

of life. All history the Native learns by heart, and must pass it on to

the little ones as they grow up. We Natives preserved our history in our

minds and handed it down from generation to generation, from time unknown,

orally. From the time human life began" (Bullchild 1985:2-3).

The oral traditions of the Nitsitapi carry them back to "time

immemorial." How long is that? Anthropologists disagree about

how long Blackfeet people have lived in their homeland. Some

say the Blackfeet have existed in the Upper Missouri country

only a few hundred years; others believe several thousand years

is

more accurate.

The

boundaries

of the territory change through time.

For now, relax. Don't get mired in this argument; instead,

let the stories carry you into a different world where quantification

is less important than experience.

|

|

|

| A Story of the Old North Trail |

| |

A century ago Chief Brings-Down-the-Sun told Walter

McClintock about the Old North Trail:

"There is a well-known trail we call the Old North Trail. It runs

north and south along the Rocky Mountains. No one knows how long it has

been used by the Indians. My father told me it originated in the migration

of a great tribe of Indians from the distant north to the south, and

all the tribes have, ever since, continued to follow in their tracks.

"The Old North Trail is now becoming overgrown with

moss and grass, but it was worn so deeply, by many generations of travelers,

that the travois tracks and horse trail are still plainly visible...

"In many places the white man's roads and towns have obliterated

the Old Trail. It forked where the city of Calgary now stands. The right

fork ran north into the Barren Lands as far as people live. The main

trail ran south along the eastern side of the Rockies, at a uniform distance

from the mountains, keeping clear of the forest and outside of the foothills.

It ran close to where the city of Helena now stands and extended south

into the country inhabited by a people with dark skins and long hair

falling over their faces.

"My father once told me of an expedition from the Blackfeet that

went south by the Old Trail to visit the people with dark skins. Elk Tongue

and his wife, Natoya, were of this expedition, also Arrow Top and Pemmican,

who was a boy of 12 at that time. He died only a few years ago at the

age of 95. They were absent four years. It took them 12 moons of steady

traveling to reach the country of the dark-skinned people, and 18 moons

to come north again. They returned by a longer route through the "High

Trees" or Bitterroot country, where they could travel without danger

of being seen. They feared going along the North Trail because it was

frequented by their enemies, the Crows, Sioux, and Cheyennes.

"I have followed the Old North Trail so often that I know every

mountain, stream, and river far to the south as well as toward the distant

north" (Brings-Down-the-Sun in McClintock 1992: 434-437).

Along the

Rocky Mountain front. |

S. Thompson photo

|

|

| |

| |

| Reckoning Time |

| |

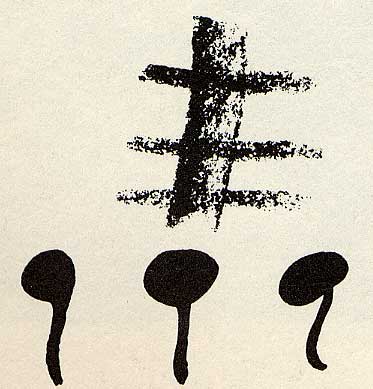

Winter count is a way of reckoning time, a tribal calendar

of history. A long-ago person sat down to record the memorable

events from a round of seasons on a tanned buffalo hide.

"The winter count is an important record.

Not only does it give us a historical record of the Blackfeet

people greater than that previously recorded, but also

an

insight into these events. The memories of those elders

still living have been added to the events as well as those

of past

researchers. It was the feelings of people that started

this record, and they should be carried with it" (Raczka

1979:5).

Original hide drawings for this winter count were made by

five contributors from the North Piegan, or Pikuni. The drawings

include the period from 1764 through 1924. Paul Raczka, with

credit given to elders, compiled the images in a book from

which the following examples are taken. (This winter count

recorded by the Rev. Cannon Haynes in journal form was given

by Bull Plume.)

|

|

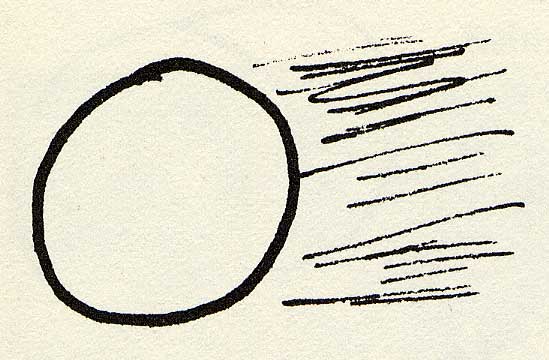

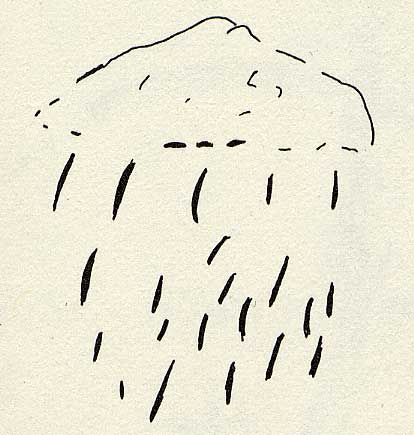

1778—The great wind. |

|

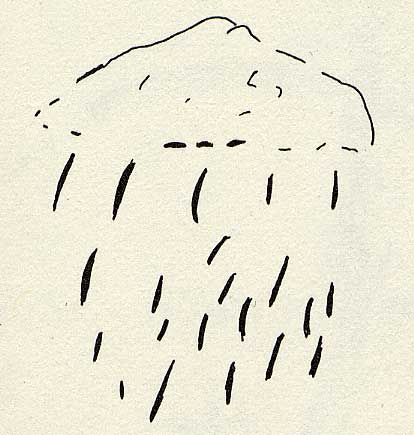

1779—When it hailed

in winter. |

|

|

|

1782—When they took the shield.

The capture of a shield was an important coup. Being both an article

of war and a religious item, the shield was a much sought-after trophy,

especially those of the Crow tribe, which were highly decorated similar

to Blackfoot shields. |

|

1801—When we took

the stars and stripes from the River Indians.

Capturing a flag from the enemy was considered an important act.

Flags were regarded as having power as war medicines. The people

referred to are Pend d'Oreilles, called Niitugta tapi (River

People) in Blackfoot. |

|

|

| Hugh Dempsey, a scholar of Blackfeet

culture, noted the significance,"that an

American flag should be captured by the Piegans

four years before the Lewis and Clark expedition

came west. The area was still considered part

of the Spanish possession, but there were rumors

and indications from David Thompson that Americans

had penetrated the area even prior to Lewis and

Clark." (Dempsey: personal communication

to Raczka, 1978) |

|

|

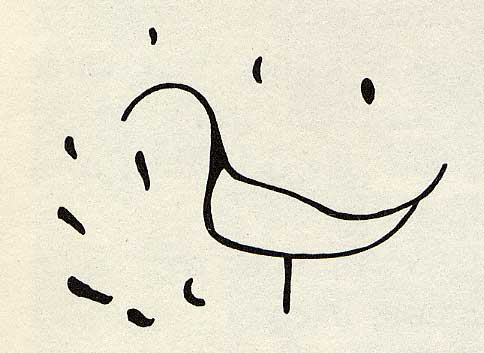

1805—When the crows died. This refers

to the bird, not the tribe.

|

|

1806—Many foolish

children were killed. [Children had wandered

away from the camp and

drowned.] |

|

|

|

1808—Getting paint and taking captive

(near Turtle Mountain, by Crow Indians).

There is a location for getting earth paint on the Castle River

near

Turtle Mountain.

(Raczka: 1979) |

|

Source:

Raczka, P. M. Winter Count: A history of

the Blackfoot people. Calgary: Friesen

Printers for Oldman River Culture Center, 1979.(from

original hide drawings) |

|

|

| |

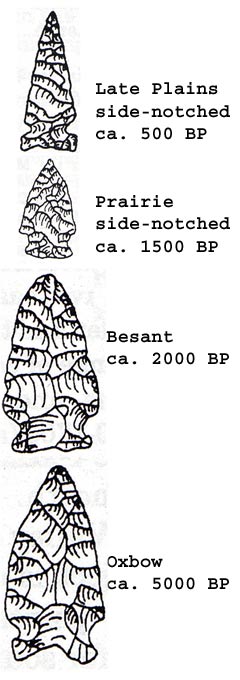

| Archaeological Evidence of the Blackfeet |

| |

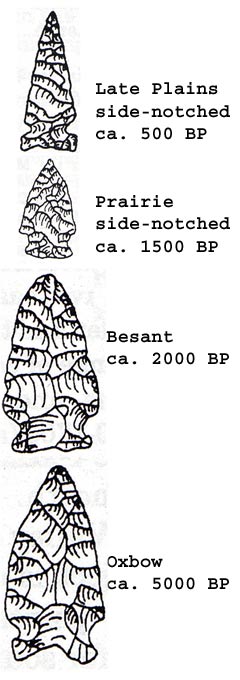

Archaeological evidence indicates that the

Blackfeet people have lived in the region of the Northwestern

Plains for at least 6,000 years.

Stylized stone projectile points are the key

indicators of ancestral Blackfeet sites. Their territory was

not constant through these millennia. It changed within the

region depending on shifting food resources and relationships

with neighbors.

One significant campsite, located alongside an

oxbow meander of the Sun River near the Great Falls, was used

by Blackfeet people off and on for thousands of years. Meriwether

Lewis came close to this site when he was exploring the area

during the summer of 1805.

Although the Piegan, Kainah, and Siksika bands were

spread over a large territory, even larger than the Blackfeet homeland

of historic times, they centered around the Sand Hills of southwestern

Saskatchewan. There they buried their loved ones. Blackfeet people

still talk of their spirits' returning to the Sand Hills after

death. (Greiser, 1986, 1994; Reeves, 1969). |

Image courtesy of S. Thompson. |

|

| |

Background ©Apiisoomahka

Wm. Singer III, 1993;

used with permission from Red Crow College |

|

|

|